Global debt has hit a record high of $152 trillion, weighing down economic growth and adding to risks that recovery could turn into stagnation or even recession, the International Monetary Fund has warned.

In a worst-case scenario the IMF also fears that a wave of populist politics across the US and Europe could send globalisation into reverse with protectionist policies hitting international trade, investment and migration, sending the world plunging into a prolonged period of stagnation.

The warning came after the IMF cut its growth forecasts for a series of countries around the world, leaving Britain the fastest growing economy in the G7.

ADVERTISING

It is urging governments to help troubled banks in the worst-affected parts of Europe, spend more money on boosting economic growth where possible, and reform economies to increase GDP – as well as pushing to keep borders as open as possible.

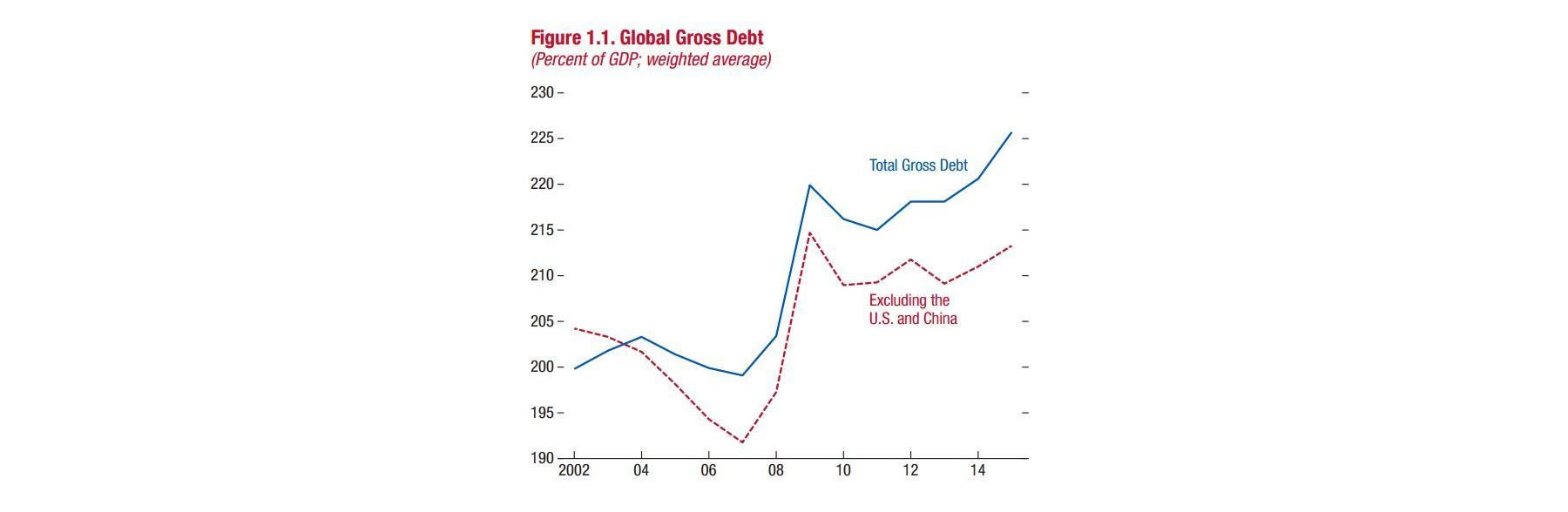

World debt is at a record high, more than replacing the dip in borrowing which followed the financial crisisWorld debt is at a record high, more than replacing the dip in borrowing which followed the financial crisis CREDIT: IMF

“At 225pc of world GDP, the global debt …is currently at an all-time high. Two-thirds, amounting to about $100 trillion, consists of liabilities of the private sector which can carry great risks when they reach excessive levels,” the IMF said in its fiscal monitor.

“The sheer size of debt could set the stage for an unprecedented private deleveraging process that could thwart the fragile economic recovery.”

This debt burden is mounting at a time when slow growth means inflation and interest rates will remain low, making it hard for companies, individuals and governments to earn their way out of debt.

A combination of low growth, high debt and weak banks could push the world in a dangerous financial and political direction, the IMF said.

“The political climate is unsettled in many countries. A lack of income growth and a rise in inequality have opened the door for populist, inward-looking policies,” the IMF warned in its global financial stability report.

“These developments make it even harder to tackle legacy problems, further expose economies and markets to shocks, and raise the risk of a gradual slide into economic and financial stagnation. In such a state, financial institutions struggle to sustain healthy balance sheets, which weakens economic growth and financial stability.”

The IMF does not name politicians directly, but the campaigns of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton have seen a marked turn against globalisation in the US, while EU leaders have struggled to agree a trade deal with either the US or Canada.

In a hypothetical scenario imagining a wave of protectionism, the IMF said “These initiatives limit or reverse international trade and financial integration, generating a sell-off in stock markets on profitability concerns and reduced risk appetite, with the real equity price falling by 20pc in the eurozone, the UK and the US over two years,” illustrating the scale of the danger.

Banks would be crushed by the economic slump while private consumption and business investment would also fall, hitting growth further. “Protectionist measures in Europe and the US [would] ultimately generate secular stagnation, given constrained macroeconomic policy responses,” the IMF said.

Meanwhile it called for action to help troubled banks deal with their problems, reducing bad debts in the short-term, and kick-starting the supply of credit to boost longer-term growth.

Countries such as the UK and US have reduced their private sector debts only for government debts to soar, the reports said, while eurozone countries tried to hold down government debts but found their banks struggling under the weight of bad loans to the private sector.

Those countries which can afford to should subsidise good borrowers and help banks absorb the cost of writing off bad loans, the IMF suggested. Structural problems in the banking market mean that even in an economic upswing, more than 25pc of banks in the rich world will still struggle.

As a result the IMF proposes that the weakest banks should be shut down or merged into larger, stronger entities.

Closing one-third of all bank branches would also help modernise and rationalise the industry, saving $18bn of costs in the process, the IMF said.

Spending money on banks has not always been popular, but the IMF believes it would be powerful: “It can alleviate the recessionary impact of private sector deleveraging and result in lower public debt, compared to a no-policy-action scenario. It is also more effective than other standard fiscal stimulus measures. For the same fiscal cost, the output effects are about four times larger.”

Q – How did we get here?

The world did not rack up $152 trillion of debt overnight. This enormous debt is the combination of a borrowing binge in the years before the financial crisis, followed by policies to try to get out of the recession which followed the boom.

Western economies in particular borrowed heavily in the boom years. In the UK and the US, governments stepped in to bail out banks, meaning the financial sector recovered – but governments ended up with huge debts instead.

The eurozone tried a different route which left some of its governments with less debt, but many of its banks are still in trouble. Both are difficult positions to be in, especially when economists now want governments to spend more money to try to boost the economy.

Q – Is it a problem?

Debts like this are never likely to disappear. Governments rarely run budget surpluses, so they typically add to their borrowing over the years.

It does not have to be a problem – as long as the economy is growing quickly. Unfortunately, the world economy is not growing fast, and some of the most indebted economies in the western world are very weak.

Just as a household runs into trouble when it has big debts but a flat or falling income, so governments can struggle when GDP is flat. Over time interest payments mount up, adding to the debt even when the economy is not growing.

Q – how can we get out of this problem?

The IMF hopes that there are a couple of options to get out of this, though neither is painless.

Central banks have slashed interest rates to record lows, which helps governments because their borrowing costs are very low. This gives even indebted governments a little bit of breathing space.

Officials at the IMF recommend governments which can afford to spend more, do so – those with bad banks should help the banks clean up their bad loans, as well as forcing inefficient companies to merge and cut costs.

Governments with good banks could spend more on infrastructure to create jobs and boost the long-term potential of the economy.

And more crucially, they should get rid of the red tape which strangles economies, freeing up over-regulated jobs markets, slashing barriers to international trade and encouraging research and development to boost productivity growth.

Governments have been urged to take these steps for several years, however, and many have met political resistance.

If the IMF’s fears come true and governments move in the opposite direction, closing borders and clamping down on trade, then a gloomy future of permanent debt and economic disappointment lies ahead.